The theme of this issue, ‘no-self(anattā)’, is probably one of the most misunderstood concepts in Buddhism.

It is an issue that has come up many times in the history of Buddhism in the past as well as in the present day.

The misconception is the idea that Buddhism preached no-self and therefore denied the existence of an afterlife or spirit (soul).

In short, it is the idea that when you die, you become nothing. There are many modern monks and Buddhist scholars who take this view and position.

However, if ‘everything ceases to exist at death’, then it is materialism and ceases to be a religion.

This is all the more ludicrous if Buddhism, one of the world’s three major religions, is materialist.

Even for traditional Buddhist monks, this may be fraudulent if they are conducting funerals and Obon ancestor memorial services even though they “do not believe in the spirit”.

What happens to people who do not believe in spirits after death?

As a practical matter, people who do not believe in the afterlife or the spirit cannot return straight to the heavens after death.

The afterlife is a world where ‘perception is everything’, so for those who are aware that there is no afterlife and that spirits do not exist, such a world is actually unfolding.

This means that many people do not even return to the other world, but become floating spirits, roaming the earth, and in some cases become haunting spirits, possessing people in this world and doing all sorts of evil things to them.

In particular, it is not easy to requiem the souls of those who have been poisoned by scientific universalism and who are convinced that they will never accept the afterlife, spirits and so on, and are doing their best to do so.

Alternatively, there is a pattern where even spirits who have accepted that they are apparently dead, but with zero knowledge of the spiritual dimension, still have nowhere to go and have no choice but to cling to their graves.

In this sense, in modern Japan there is a tendency to say things like “No need for funerals or graves! However, there are cases where people manage to awaken to their spiritual selves through funerals, so it is important to hold a proper memorial service.

Also in this life, those who believe that there is no afterlife, no spirit, and that everything ends when they die, tend to drift either towards ephemeral hedonism or pessimism.

‘He who deviates from the only law of reason, who speaks falsehood, who ignores the world of the other shore, is not free from any evil.’ (Dhammapatha, 176)

And it is fair to say that it is very difficult for people who live by such values to return to a heavenly world after death.

Even if we think in utilitarian terms, we can live better if we acknowledge the afterlife.

In the first place, an idea that does not presuppose an afterlife or a spirit is a state of abandoning its premises as a religion.

And we must not forget that such a ‘religion lacking substance’ can never have an ethical basis.

Why the switch to the logic that no-self = no spirit?

In his book, Akira Masaki traces the origins of the modern theory of ‘no-self = no spirit’.

I will quote the relevant section (I am responsible for the English translation).

Around the 1930s, Hakju Ui (1882-1936), a member of the Department of Indian Philosophy at the University of Tokyo, who was in a leading position in Buddhist studies at the time, argued that ‘no-self theory’ means that there is no ‘self’, and ‘self’ means spirit, so ‘no-self theory’ is thus a denial of spirit.

Masaki also points out that there are at least two statements in the Sanyuttha Nikaya that can only be interpreted as an acknowledgement by the Buddha (Gautama Buddha) of some kind of existence after death.

I believe that the poisoned water flowing through modern Buddhist studies and Buddhist circles is of the same origin as Masaki has pointed out.

* Incidentally, more than 2,000 years ago, during the period of tribal Buddhism in India, the ‘Sarvastivada’ sect also played a central role in turning no-self into a substantial materialist theory.

In this essay, I would like to consider the issue of the soul in relation to the theory of no-self from a different angle to Masaki’s, from the middle way of presence/absence and the middle way of eternalism/annihilationism.

Incidentally, the sociologist Daisaburo Hashizume, in discussing this issue on one of his websites, writes: “Buddhism, unlike monotheism, has freedom of thought. You can think whatever you want,” etc., but that is not true.

It is true that Buddhism has a generous doctrinal interpretation, but there are firm doctrinal axes such as the three Dharma seals, the law of dependent co-arising, the Middle Way… so there is no such thing as “it doesn’t matter what you think”.

Atman and Anatman

“Brahman equivalent to Atman(Brahma-self-unity)” philosophy

First, let me explain how the idea of ‘no-self’ was preached.

Before Buddhism, Brahmanism (the religion of the Vedas) dominated Indian thought with the idea of ” Brahma-self-unity”.

Brahman is the supreme deity of Brahmanism.

The idea that Brahman and the Self are one in essence is the idea of Brahma-self-unity.

The “self” here is called “Atman” in Sanskrit.

By Self = Atman, we are not talking about our ordinary so-called ‘self’, but about the “True Self”, which is at the deepest level of our self-consciousness.

That is, the idea that when we delve into the essence of our ‘self’, we come across the true self or Atman, which is identical in essence with Brahman, the fundamental principle of the universe, is Brahma-self-unity.

The Buddha preached “no-self” as the antithesis to the idea of Brahma-self-unity. The Sanskrit word for no-self is “anatman”.

Incidentally, Brahmanism is the religion that became the mainstay of present-day Hinduism. Brahmanism gradually became Hinduism while absorbing indigenous Indian beliefs.

Is Brahma-self-unity the same as “all things have the Buddha nature”?

By the way, from the point of view of Japanese people who are familiar with Mahayana Buddhism, it seems strange that the Buddha rejected the idea of “Brahma-self-unity”.

In Buddhism, there is the idea of “all things have the Buddha nature”, which means that we have the same nature as the Buddha in our essence.

This is almost the same idea as the earlier “Brahma-self-unity”.

The “all things have the Buddha nature theory”, also known as the “Tathāgatagarbha theory”, is said to have emerged in the history of Buddhism not during the Buddha’s lifetime, but in the Mahayana period.

This means that Buddhism, from the time of the Buddha’s Buddhism, through the period of the tribal schools of Buddhism, and with the rise of Mahayana Buddhism, has arrived at an ideology that is almost exactly the same as the “Brahma-self-unity” that the Buddha originally denied, the theory of Buddha-nature.

However, this does not mean that Buddha Shakyamuni did not preach ” Buddha-nature theory”.

This is in effect the same as the Buddha’s Buddha-nature theory, since the Buddha preached that anyone can become an Arhat by refining oneself through practice and renouncing attachments.

Therefore, it can be said that the Buddha nature theory and Tathāgatagarbha theory that emerged in Mahayana Buddhism was more of a return to the origin, a return to the true intention of the Buddha.

A genuine reform movement necessarily has an aspect of a restoration movement.

For example, Martin Luther in 16th century Germany led the Reformation with his simplism of ‘Bible only’, ‘Faith only’ and ‘Grace only’, which is also a strong aspect of Christianity’s return to its origins and restoration movement.

Japan’s Meiji Restoration, while also an innovation, was a ‘restoration of the monarchy’.

Mahayana Buddhism similarly had an aspect of a restoration movement to ‘return to the true intention of the Buddha’, at least until about the middle of the Mahayana movement.

Why did the Buddha preach no-self?

Now, then, why did the Buddha preach the idea of no-self?

This was because the “Brahma-self-alone” philosophy of the time had become a skeleton, leading to the arrogance of the Brahmin priestly class, who believed that “I am great”.

It is just the same structure as the scribes of Jesus’ time, who exalted themselves on the basis of the law and created discrimination.

India has a caste system now and once upon a time.

The caste system is an ideology that broadly divides people into Brahmin (priestly class), Kshatriya (warrior class), Vaishya (commoner class) and Shudra (servant class) statuses, which are fixed at birth and cannot be changed.

In response, Shakyamuni put forward the ‘equality of opportunity’ theory, which states that a person’s greatness and worth are not determined by birth, but by thoughts and deeds.

The idea of cause and effect was converted to ‘value as a person’ rather than status.

And in the process, he challenged the core of Brahmin thought, “Brahma-self-unity” or the idea of Atman, with the idea of Anatman, or no-self.

“You think of the self as ‘self-possessed’, but what is this self? Self is a transient thing that cannot exist by itself”, Buddha asserted.

This is how the idea of non-self was preached.

Incidentally, though, Buddhism almost disappeared from India after Muslim raids around the 13th century, but in modern India, the number of people converting to Buddhism is gradually increasing.

This movement is called “neo-buddhism” because Buddhist ideas of equality are being reconsidered in the face of the practical difficulty of breaking the caste system, but this is not something new in terms of ideology. It is a political movement.

Although it shares the same name as our website Neo Buddhism, there is no relationship at all.

No-self or Not-self?

So, for Buddha, he was preaching the idea of no-self in order to break through the ‘attachment to self’.

However, when translated as ‘no-self’, it is inevitable that the word tends to go along the lines of ‘no-self ⇢ no soul’, as mentioned at the beginning of this article.

Hajime Nakamura, a world-renowned authority on Buddhist studies, argued that anatman should be interpreted as ‘not-self’ rather than ‘no-self’.

In short, it is not I (self).

The Buddha denied the “false self” and the “self caught up in worldly desires”, and this is the ” not-self” that Hajime Nakamura claimed.

The self, which is the subject of practice, is rather positively acknowledged.

Indeed, this interpretation of ” not-self” seems to me to be a better explanation of the Buddha’s true intentions.

However, the interpretation of not-self is a bit of a compromise, and does not answer the question, “So, in the end, when we say ‘not-self’, is there a spirit or not?

Is there a “self” or not? – The Middle Way of existence/non-existence

Checking whether the Right View of the Noble Eightfold Path has been inspected

Now, those who think like the Buddhist scholar Hakuju Ui , whom I introduced earlier, are,Rather than having reached the conclusion that there is no spirit as an effect of their pursuit of ‘no-self’, I think their order of thought is that they don’t believe in spirits, or don’t want to believe in spirits, so they jump to an interpretation of no-self that is linked to no-soul.

Here, there is first of all an inadequate inspection of ‘whether one’s values are free from the preconceptions and prejudices of one’s own time’, i.e. the starting point of the Noble Eightfold Path, the Right View.

And even high priests and renowned scholars are often caught up in such prejudices.

Self as the premise of ‘Self-Lighting’

First, as a starting point, let us consider the issue of whether there is or is not an ‘I’.

If the word ‘no-self’ is read literally, it can be read as there is no I.

However, if there is no self at all, then there is no subject to practise either, which means that Buddhist practice itself is not possible.

The Buddha’s last will and testament (the Nirvana Sutra) preaches self-lamping and Dharma-lamping.

This means that after the Buddha’s death, one should “make oneself the foundation” and “make the Dharma the foundation”.

If the self is nothing, then the basis for “self-light” cannot be established.

Six Supernormal Knowledge (Abhijñā)

The Buddha is said to have attained enlightenment and to have attained the “six supernormal knowledge”.

Among the six supernormal knowledge are “Remember one’s former abodes” and “Divine eye”.

- Remember one’s former abodes : causal memory, that is, recalling one’s own past lives

- Divine eye : knowing others’ karmic destinations

In simple terms, this means the ability to see into a person’s past and future lives.

This clearly recognises reincarnation. And in order to reincarnate, there must naturally be a reincarnating entity, i.e. a spirit soul.

Thinking in The Middle Way of existence/non-existence

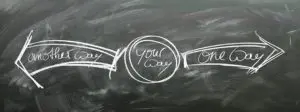

So, even with regard to no-self, it is still necessary to think in the middle way here, rather than simply thinking, “Since it says that there is no self, there must also be no spirit”.

Thinking in the middle way in everything. This is the orthodoxy of Buddhist interpretation.

We have already discussed ‘Oneness, Buddhism, and the Universe. And to the Enlightenment of Neo Buddhism” article, we have discussed Reality and Phenomena.

Each of us is a ‘single phenomenon’, so we are impermanent in time and no-self in existence.

The body and mind change from moment to moment (impermanence), and the body itself is dependent on other entities such as food and air (no-self), so it can be said that it is not an entity.

The main reason for the Buddha’s emphasis on non-self is practical: ‘to break the attachment based on ego-consciousness, which is the cause of suffering.

In this case, the ‘self’ is the self that has moved away from the awareness of being part of reality and also from the awareness of being connected to other phenomena.

In independent ego-consciousness, a ‘fundamental anxiety of existence’ is invariably induced.

In an attempt to temporarily alleviate this ‘fundamental anxiety of existence’, people desperately seek relative superiority over others, but this is not a fundamental solution.

So, in order to cut off the root of suffering, the Buddha preached a fundamental ontology that the self should not be seen as an ego that is independent of the whole (reality) and others (phenomena).

And it is both an ontology and a powerful practical theory.

Hence, as shown below, it is the “middle way of existence/non-existence” which I believe is the legitimate interpretation.

- The self can be said to “exist” in the sense that it is an entity that bears a part of reality and has a certain individuality and identity.

- The self can be said to be ” does not exist” in the sense that it cannot be an independent entity that is separate from reality and others.

What should we think about Skandhas’ temporary aggregation?

In Buddhism, the elements that make up human beings are divided into five categories. These five are called Skandhas in Sanskrit.

In English, Skandhas is sometimes translated as “five aggregates.

Skandhas are the following five

- form (or material image, impression) (rupa)

- sensations (or feelings, received from form) (vedana)

- perceptions (samjna)

- mental activity or formations (sankhara)

- consciousness (vijnana)

Some Buddhist scholars explain that since human beings exist as a “temporary set” of these five elements, when the set ceases to exist (i.e., when we die), it dissipates into the clouds, and this is what is called ” no-self.

However, in the sense of “tentatively assembled,” it is not fixedly assembled at this moment either.

From time to time, our physical bodies and the contents of our minds and spirits change, don’t they?

Therefore, the ” tentative set of Skandhas” should be seen only as a practical teaching to break the attachment that the Self as a phenomenon is not an entity.

After all, do we have a soul or not? – Thinking in terms of “the middle way of being cut off and being continued

The “poisoned arrow parable” and the “unanswerable questions” are not grounds

In reading some Buddhist books, we notice that some authors cite the “Parable of the Poisoned Arrow” and the “unanswerable questions” as the basis for their argument that “the Buddha avoided discussing the existence of the afterlife and metaphysics.

Let me explain the “Parable of the Poisoned Arrow” in a nutshell.

On one occasion, a monk Malunkyaputta asked Shakyamuni Buddha such appropriative questions as “Does life continue after death?” and “Is the universe infinite or finite?

The Buddha replied, “If a poisoned arrow is stuck in you and you think about anything other than healing, the poison will turn, so you must remove the arrow first.

The Buddha’s true meaning is that life passes away while we are asking and answering metaphysical questions. Rather, the first priority is to “solve the problem of one’s own life and death.

With this, many Buddhist books claim that the Buddha was not involved in metaphysical issues.

However, this should not be taken to mean that the Buddha denied the afterlife or the spirit, but rather that he was preaching in consideration of the characteristics of the monk Malunkyaputta.

“unanswerable questions” means “the Buddha was silent on metaphysical arguments”.

This “unanswerable question” is similar to the “Parable of the Poisoned Arrow,” and it may be that the Buddha sometimes gave “unanswerable questions” according to the characteristics of the people to whom he was preaching.

In India, now and in the past, “the other world, spirits, reincarnation,” etc., were all generally acknowledged, you know.

Also, Indians are very fond of metaphysical discussions.

Since this is the case, the Buddha sometimes decided that it was not necessary to preach too deeply about the spiritual world or the spirit soul, or in metaphysical discussions.

For some people, such topics would degenerate into mere hobbyistic discussions.

The above-mentioned monk named Malunkyaputta was of that type, and that is why the Buddha/Shakti told the analogy of poisoned arrows and kept “unanswerable questions”.

That is how it is.

There are any number of these issues in contemporary spirituality.

Rather than thinking, “What about Atlantis?” or “What about the 23rd dimension?” we must first overcome the problem of life and death as our own existential problem.

Buddha preached “Gradual Instruction.”

“Gradual Instruction” is a preparatory teaching before the Buddha preaches the Four Noble Truths or other advanced teachings.

The Buddha often preached three theories to lay believers.

- Theory of Almsgiving (dāna-kathā)

- Theory of Precepts (sīla-kathā)

- Theory of Birth into Heaven (sagga-kathā)

This is a very simple sermon for lay believers.

If there were no afterlife or soul, then the “Theory of Birth into Heaven” would be completely false.

Without a spirit, there would be no “subject of birth into heaven.

There can be no interpretation that the Buddha, who preached “Do not lie” in the Five Precepts, preached lying in the Basic Sermon.

Therefore, in light of the basic doctrine of the Buddha, the assertion that “Buddhism denied the spirit” is a logical error.

Thinking in the “Middle Way of Sassatavada/Ucchedavada

So let’s still think in the Middle Way here.

- Sassatavada: Eternalism

- Ucchedavada: Annihilationism

The truth lies in a Middle Way that rejects these two extremes.

The view that when the body dies, the soul ceases to exist clearly falls into Annihilationism.

There are numerous Buddhist texts that say things like, “The Buddha did not in any sense recognize the eternal and immortal soul after death; he denied Eternalism.”

But here is a subtle shifting of words. It is “eternal and immortal soul.”

If the soul survives after death, does that equal “unchanging”?

The soul, as a “phenomenon,” also changes after death. It is both impermanent and no-self.

So the equation that the view that there is a soul after death falls into Eternalism is clearly a logical error.

The interpretation “the soul continues and changes” is sufficient for the Middle Way of Sassatavada/Ucchedavada.

Hence, the conclusion is: “The existence of a soul does not conflict with Annihilationism. Rather, if you deny the soul, you fall into Annihilationism, which is not Buddhism“.

Buddhism and religion are the foundation of ethics. The validity of ethics cannot be guaranteed without the existence of the next life or spirit.

For, if there is no afterlife (if life is limited to this life), then the law of cause and effect is not complete.

It is only because we can believe in the spirit, the next life, and reincarnation that we can be confident in the law of cause and effect.

Let’s savor the words of the Dhammapatha once again.

‘He who deviates from the only law of reason, who speaks falsehood, who ignores the world of the other shore, is not free from any evil.’ (Dhammapatha, 176)

Comments